Winter snow is a welcome sight at Lake Tahoe, particularly since four of the last five winters were exceptionally dry. But as much as we all enjoy skiing or riding and as much as our towns depend on winter tourists to keep our economy going, there is a hidden cost to a return to winter: stormwater, and the pollution that it transports into Lake Tahoe.

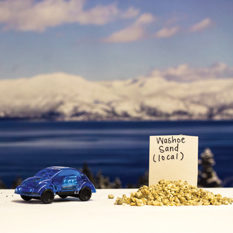

Lake Tahoe is designated an outstanding national resource water by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, affording it protections that most lakes its size don’t have. EPA, however, also lists Tahoe as “impaired” by fine sediment pollution and an excess of the nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus. Both are carried into Lake Tahoe when rain and snow washes off Tahoe’s roads and parking lots. Unlike grains of sand, which sink, fine sediment particles — each smaller than the width of a human hair — remain suspended in the lake, reducing its clarity. Plants need nutrients to grow, but excessive nutrients fuel the growth of algae.

Under federal law, Tahoe’s special status requires agencies in the basin to reduce the inputs of these contaminants and restore Lake Tahoe to its historic clarity. When Charles Goldman began dropping the Secchi disk in the lake in the 1950s, clarity reached over 100 feet in depth. It worsened over the decades, but for the past four years, the Tahoe Environmental Research Center’s clarity measurements at the center of Tahoe have been better than any other year in the previous decade. It’s no coincidence that these same four years were a record drought.